Folds, Scans, and Laziness

Lazy evaluation

Haskell is a lazy language. This means that “expressions are not evaluated when they are bound to variables, but their evaluation is deferred until their results are needed by other computatations.”Haskell wiki.

Consider as an example the following implementation of quicksort.

quicksort [] = []

quicksort (p:xs) = (quicksort lesser) ++ [p] ++ (quicksort greater)

where

lesser = filter (< p) xs

greater = filter (>= p) xsIf we evaluate head $ quicksort [5, 3, 6, 1, 7] in ghci, evaluation will proceed in reverse order compared to any non-lazy language. A language like Python would first sort the list, then extract the head, and finally print the result. In Haskell, ghci would first attempt to print the first character of output. To do so, it must evaluate the head of the sorted list, and will therefore generate the first element by completing only those operations necessary to sort out the first element. First it will split the list into the following.

[3, 1] ++ [5] ++ [6, 7]Then, since it only needs the first element it will just sort [3, 1] to extract 1 as the result, without ever concatenating or sorting the other sub-lists.

Thus, if we run take k $ quicksort xs, thanks to lazy evaluation only the first k elements will be sorted. Indeed, this will take \(O(n + k \log k)\) time, whereas a non-lazy quicksort would always take \(O(n \log n)\) time.

Folds

So far, we have seen two higher order functions map and filter that process lists using other functions. Each of these captures a natural class of operations, with map operating element-wise on a list and filter … filtering a list.

A fold is a higher order function that captures the operation of summarizing a list’s elements as a single value. In other contexts, a fold is sometimes referred to as a reduce.

Let us begin by considering an example. Assume we have a list of integers and wish to sum them. We could restate this problem as accumulating the list values into a “total” value. For example, to sum [2, 4, 5, 1] you would begin having accumulated a total of 0 and successively add 2, 4, 5, and 1. This process is captured by the following use of the foldr function.

Here, foldl applies (+) successively between the accumulated value (beginning with the initial value 0) and the values in the list from right to left.

In general, a fold takes a function, an initial “accumulator” value, and a list, and repeatedly applies the function between the accumulated value (beginning with the initial value) and returns the final accumulated value. The foldl function applies this function taking elements leftwards through the list. foldr, does the opposite, taking values rightward (i.e. from the back). Besides foldl and foldr the standard library provides foldl1, and foldr1, which take the first and last value of the list as the initial accumulator respectively.

In the general case,

foldl f acc [v1, v2, v3] == (f (f (f acc v1) v2) v3)

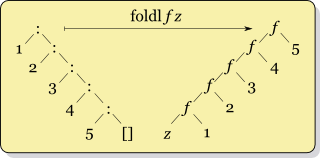

foldr f acc [v1, v2, v3] == (f v1 (f v2 (f v3 acc)))The fold functions can be seen as collapsing the list datastructure as follows.

Note that the function argument for the left fold foldl takes the accumulator as its first argument and the list elements as its second, and the right fold foldr does the reverse. This is reflected in the type signatures and implementations of both functions.

foldl :: (b -> a -> b) -> b -> [a] -> b

foldl f acc [] = acc

foldl f acc (x:xs) = foldl f (f acc x) xs

foldr :: (a -> b -> b) -> b -> [a] -> b

foldr f acc [] = acc

foldr f acc (x:xs) = f x (foldr f acc xs)Also, note that the type of the accumulated value and the list values need not be the same (as they are in the sum example). For instance, you could check a property holds for all the elements in the list by having a boolean accumulator and setting it to false once some element does not satisfy a condition.

ghci> foldl (\acc x -> acc && even x) True [2, 4, 6]

True

ghci> foldl (\acc x -> acc && even x) True [2, 4, 5, 6]

FalseScans

A scan is like a hybrid between a map and a fold. For example,

scanl is similar to foldl, but returns a list of successive folded values from the left.

Note that last (scanl f z xs) == foldl f z xs.